An Ounce of Prevention and a Dash of Mitigation

Rental Assistance and Single Room Occupancy as Sustainable Homelessness Strategies

The Oregon Legislature’s recent homelessness prevention strategy lacks a sustainable foundation. The state rental assistance program does not have a dedicated funding stream. Its tenant protection measures accomplish their goal but only at the high cost of worsening the housing supply problem. And the proposed housing supply remedy will take decades to significantly increase and diversify the available inventory. Instead of nibbling around the edges of the problem, we should employ two more effective strategies to get to the heart of the matter. Building a sustainable funding source for short-term rental assistance programs and adopting a guarantor model to support the use of existing single family residences in single room occupancy would have an immediate and enduring impact. They are certainly not the complete solution, but they offer steps forward.

Build a Foundation under Short-Term Rental Assistance Programs. Many evictions result from short-term cashflow problems, rather than long-term costs. While addressing long-term affordability is important, one pre-pandemic study found that the average debt resulting in eviction was $1250, while a post-pandemic survey showed an average debt of $3,000, reflecting a relative, but short-term, rise in delinquencies during the pandemic. Even accepting the higher number, it is clear a relatively small amount of money can prevent a family from falling into homelessness. (Note that evictions are not free for landlords, either. They pay an average of about $3,500 per eviction, giving them an incentive for retaining tenants who can pay in the future.) The Legislature has taken two general approaches to this: (1) using federal pandemic funds and some state resources to provide rental assistance and (2) reducing no-cause non-renewals of long-term leases. Unfortunately, the amount available in the biannual budget varies substantially, the federal funds were temporary, and the requirements to renew leases have pushed some small landlords to sell. A Portland area initiative to fund lawyers for people facing evictions failed at the polls, likely at least in part because it did not provide any funding to solve the debt underlying the eviction.

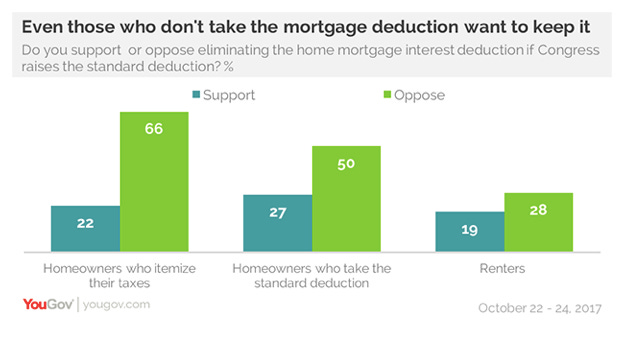

We need a permanent funding source for short-term rental assistance. Most legislative efforts to do this have targeted the popular mortgage interest deduction (MID) for elimination.

Given that fewer and fewer households actually benefit from the MID and those that do tend to be wealthier, this seems reasonable, but quickly runs into the reality that voters love it, even voters who don’t own property.

Instead, Oregon could adopt a model mixing a small flat fee on leases with a percentage fee on luxury apartment leases. When I was on Eugene’s Budget Committee, we were confronted with a good problem - our $20/year fee on leases in the city for tenant education and habitability enforcement was running a surplus. While I advocated for converting some of it to rental assistance, that ended up being beyond the scope of the authorizing ordinance. Still, on a state level, even a small fee like that could add up - a $10/month fee would likely net about $75 million a year, about twice what is currently allocated in the state budget. While a flat tax is inherently regressive, that could be offset with a progressive fee on rents over a certain level, allowing a reduction of the base amount. With about 25,000 evictions filed annually in Oregon, an annual budget of $75 million would provide about $3,000 per case to help keep people in their homes. While this doesn’t provide enough funding to address a fundamental mismatch between income and rent, it does provide enough funding to address the short-term interruptions in income that have historically resulted in many evictions.

Allow Single Family Homes to be Single Room Occupancy (SRO) Dwellings. Expanding eligibility for single room occupancy is often proposed as a solution to longer-term affordability issues. While these SRO dwellings are often thought of as boarding houses, they can also be single-family homes that are occupied by housemates. Using single family homes as SRO housing has generally failed for two reasons. First, the recently evicted lack a means of organizing to rent as a group. Second, landlords are reluctant to rent to low-income people who were just evicted.

The Oxford House model overcomes both those hurdles for people in need of a sober living arrangement, a similarly needy population. As I saw while I was a deputy district attorney in Albany, the Oxford House organization would sign a long-term lease with an owner, then sublet rooms to justice-involved folks who needed sober living arrangements. By serving as an intermediary, the organization gave the landlord the security that rental income would remain steady and damages would be covered, while providing the residents with a place to live that met their needs, had compatible housemates, and was affordable.

Traditionally, the HUD Section 8 housing program has filled this role for individuals, subsidizing the cost of individual housing. The HUD model meets the widespread cultural preference for individual housing over communal living, but Section 8 is not meeting the needs of the moment. With HUD funding flatlined and unlikely to recover, a non-profit could adapt the Oxford House model to make the best use of the available housing stock until the long-term plans for diversifying it come to fruition.

To be clear, “low income” does not mean “no income.” People with no income will continue to need more intensive support than a non-profit using the Oxford House model could provide. However, a recent California study showed that the average person facing eviction had income of about $900 per month. A non-profit model could work with even that low level of income by coordinating other forms of support for residents, such as food and social services.

Moving Forward. The United States has never really accepted housing as a human right. This led to the current environment, where the unhoused are forced into public spaces that are not designed to support them. Until we solve the housing supply problem, this state of affairs will continue. However, with sustainable rental assistance and communal use of single-family housing, we can make some progress while continuing to work on more comprehensive solutions.

Other News

A Reminder on Middle Housing. While there has been much debate about the implementation of HB 2001, mandating more ‘middle housing’, please remember that HB 2001 will not result in any low income housing. The bill is addressed to building homeownership for middle income people, not supporting low income renters.

A Perspective on Ukraine. Bret Stephens has a terrific report on a recent trip to Ukraine in the New York Times.

Editor’s Note. I started a new job last week. Your positive feedback makes me want to continue writing this column, even with my more limited time. I may not be able to publish as often, although it may become a more episodic endeavor. I also decided not to proceed with a subscription model. I’d like people to be able to access this without worrying about the cost and, while it’s permissible for a federal employee to have a ‘side gig’ like this, I prefer to keep a financial incentive out of it.